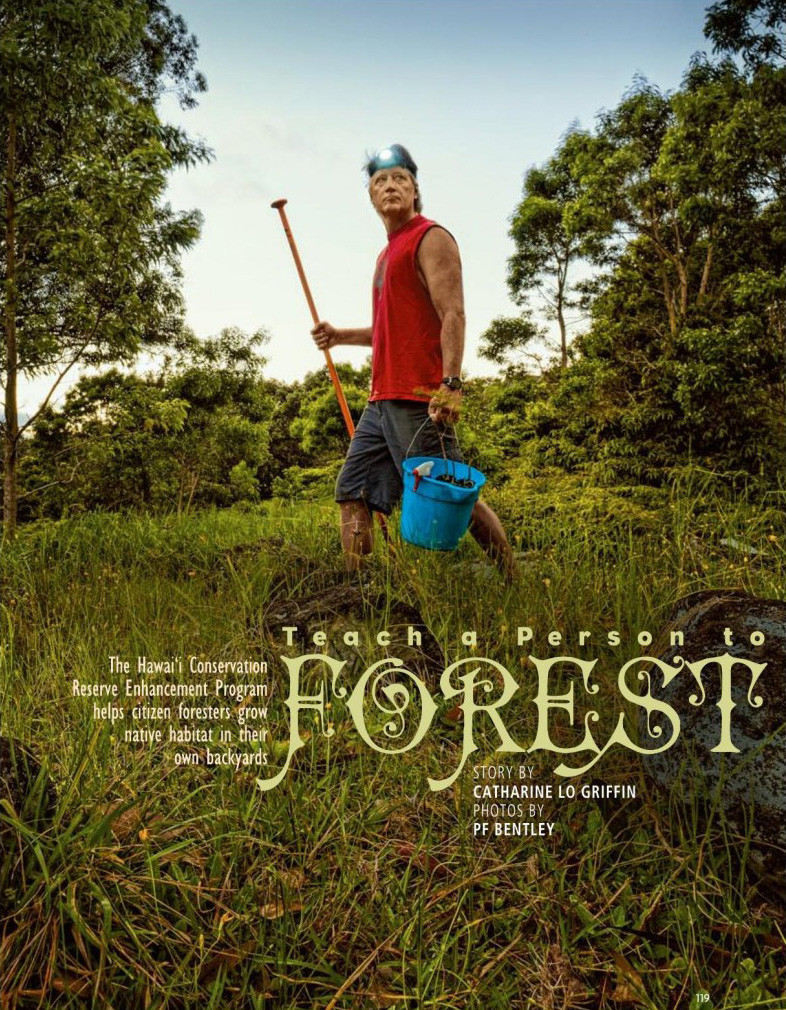

Teach a Person to Forest

"Today is the second-best time to plant a tree," says John Lindelow as we scout a spot for the koa sapling I'm going to plant. It's drizzling, as it often is here at three thousand feet above the Hämäkua coast on Hawai'i Island.

John, his nephew Matthew and horticulturalist Dave DeEsch are dressed in windbreakers and boots as we walk the trails winding through the nineteen acres of young forest Lindelow calls Ahu Lani Sanctuary. My sapling will join the more than four thousand native trees and shrubs that have been planted here at the edge of the Kalöpä Forest Reserve on Mauna Kea's northeastern slope. With care, in twenty years this native forest — decimated by cattle, pigs and invasive plants—will recover; that in turn will bring the rain, recharge the aquifer and provide habitat for wildlife.

"So when," I ask, "is the best time to plant a tree?"

"Twenty years ago," John replies.

This sort of forest restoration work is in progress throughout the Islands, and there have been great successes on public lands like Hakalau National Wildlife Refuge and Haleakalä National Park. Numerous projects are spearheaded by organizations like the Trust for Public Land and The Nature Conservancy. But Lindelow isn't with a government agency. He doesn't work for an environmental nonprofit. He's not a botanist or a forestry manager. In fact, he made his money in tech and tourism. Lindelow is a citizen forester.

When John and his wife, Roz, bought this remote property in 2002, they hoped to open a retreat center but their permit was denied. After a couple of years in limbo, they applied to the Forest Stewardship Program, one of several federal and state landowner assistance programs for forestry and wildlife habitat protection, including also the Kaululani Urban and Community Forestry, the Watershed Partnership Program, the Coastal Program and Partners for Fish and Wildlife. They were all but approved when the economic downturn hit in 2008 and money for such programs dried up. Then, in 2009, after learning about the Hawai'i Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP), the Lindelows were its first applicants.

Administered jointly by the USDA's Farm Service Agency, the Natural Resources Conservation Service and the state Division of Forestry and Wildlife (DOFAW), the program helps private landowners reforest environmentally sensitive lands. Landowners are reimbursed for a portion — around 50 percent, and in combination with other subsidies, as much as 90 percent — of the cost to plant backyard native forest. CREP-eligible lands must be "riparian buffers," which includes all channels to the sea: perennial and intermittent streams, gulches, even lava tubes.

"When we were talking about establishing the program, it really was about addressing the threat to our coral ecosystem," explains cooperative resource management forester Irene Sprecher of DOFAW. "There's a lot of sedimentation, a lot of soil runoff after every rain that ends up in the ocean. Establishing buffers along waterways helps to hold the soil and filter the water that does run through. Also, the trees slow the rainfall down so it gets absorbed instead of hitting the ground so hard and rushing out."

But landowners on the whole are reluctant to create these buffers, Sprecher says. "Hawai'i has really high land values, especially on our agriculture lands, so a lot of producers grow crops all the way up to the edge of the stream. A program like CREP helps them take those lands out of production—they're not the best for production, anyway— by offering them a per-acre payment that can offset some of their costs. Then everyone gets a little bit of the win."

According to a 2014 Forest Service survey, 66 percent of Hawai'i Island's forests—1.2 million acres — are privately owned. CREP currently works with only 5 percent of those lands, so there's room for expansion: The program is capped at fifteen thousand acres, and there are currently eighteen CREP projects statewide that cover only 982 acres, most of them on Hawai'i Island.

Ahu Lani qualifies because it borders Kalöpä stream, which at the moment is a bed of rocks and dried leaves. "Today it's a mosquito pond. After heavy rain I've seen it like Class Five rapids," says DeEsch, who is Lindelow's partner in the project and Ahu Lani's caretaker. His dream is "to have the creeks running clean — where we could drink straight out of them."

To realize that dream, three dozen-plus volunteers from the Worldwide Opportunities on Organic Farms (WWOOF) program have worked at Ahu Lani for three to six months each. The WWOOFers helped build a mile-long fence to keep out pigs and cattle. They've cleared invasive plants, sprouted seeds, outplanted the seedlings, pulled weeds and nurtured juvenile trees. Most CREP participants must conduct such forest-building practices as part of their contract. It's physically intense, expensive work that best suits "do-it-yourself people," as Lindelow describes their team. "It's a big commitment and a labor of love," says DeEsch, "and it's absolutely the best thing I've ever done."

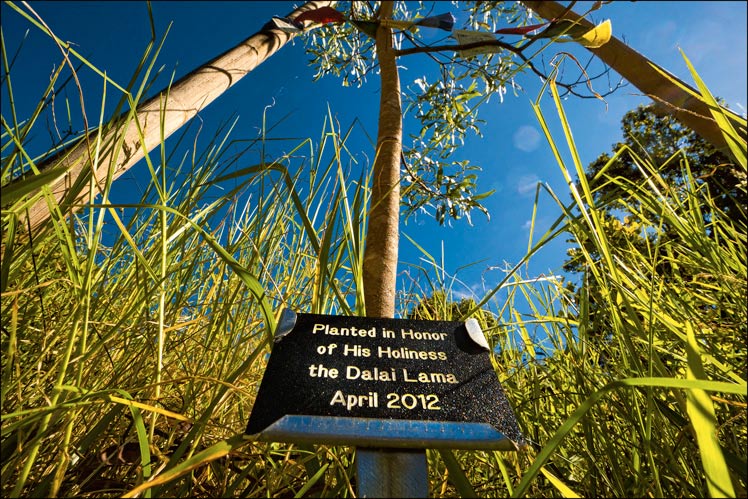

As we walk, DeEsch points to trees that others have planted. "When I see circles and groves, I see people. I don't even have to call them on the phone to be with them," he says. There's a circle belonging to students from Kua o ka Lä Charter School in Hilo. There's the Polynesian Voyaging Society Grove where Höküle'a crew members planted trees before embarking on their worldwide voyage. Ahu Lani also sponsors an Adopt-A-Tree program that invites people to commemorate special occasions by planting a sapling.

When we find the spot for my koa, DeEsch points to little red nodules on its roots and crushes one for me to sniff. It smells like ammonia—that's because those nodules pull nitrogen from the air and incorporate it into the tree's leaves and tissues. When the leaves drop, they become nitrogen-rich fertilizer; koa is one of five native nitrogen-fixing trees essential to restoring healthy forest ecosystems. I tuck the sapling into a freshly dug hole, pat it into place and give it a big drink of water. DeEsch motions toward other young koa that have been planted in this triangle. He talks about this triangle connecting to adjacent triangles and Ahu Lani eventually connecting to neighboring preserves, forming a contiguous corridor of native forest.

His eyes gleam as he imagines what all this might someday look like. "Talk about 'ohana!"

Ka Malu o Niupe'a: The Peace of Niupe'a

"Have you heard that saying, 'The land is a chief; man is its servant'?" asks Kaye Lundburg. She's referring to an 'ölelo no'eau, a Hawaiian proverb: He ali'i ka 'äina; he kauwä ke kanaka. "We really ascribe our work to that idea."

Lundburg and her partner Rod Vanderhoef's CREP project, Ka Malu o Niupe'a ("the peace of Niupe'a") covers forty-one acres near 'O'ökala, also in Hämäkua. The land was once native 'öhi'a forest, but when Lundburg acquired the property in 2012, it was choked by thickets of tough, invasive strawberry guava, some forty feet tall. "It was so thick it was literally impassable," Vanderhoef says.

If anyone can revive native forest, it's this indefatigable couple. On the acre where they base their operations, Lundburg, 72, and Vanderhoef, 65, live off-grid in a boxy two-story house painted plantation green with a red corrugated roof. Vanderhoef built a barn next to the house where visiting volunteers can stay and a giant shed to store machinery. In the yard are their vegetable garden and an egg-laying hen. As a hobby Vanderhoef keeps bees and sells the honey, Hamakua Treasures, at local stores.

Lundburg pulls out a map that shows the property divided into eight sections that split the project into manageable phases — each one will take a year to clear and plant. This is part of a plan she developed through the state's Forest Stewardship Program, which offers technical and financial assistance to nonindustrial private forest landowners interested in conservation, restoration or timber production. Having a plan is important, she says, and CREP helps with that, too. "The most critical thing is listening to what the client wants and guiding them to the change they want to see for their property," says Hawai'i Island CREP planner Alex Gerkin. With the proper planning, he says, "the rest will all fall into place."

Once the contract was signed and a perimeter fence was built, Lundburg, her son Jake and Vanderhoef got to work. They created a stream crossing so that equipment and trash could be transported. They dismantled two half-built houses, hauled out seven abandoned vehicles and two backhoes, and filled sixteen dumpsters with rubbish. They eradicated the strawberry guava—mostly by hand with heavy-duty chain saws — freeing the suffocating 'öhi'a. Using a Bobcat skidsteer they affectionately call "the beast," they pushed plant matter into giant piles they could later chip and recycle into mulch. Like Lindelow and DeEsch, they haven't done it alone; with the help of volunteers and community groups, they've planted 3,370 native plants and shrubs. (And they still have four regions left to complete.)

Even just a few years into the project, evidence of the returning forest is all around: A vine of maile pops out of an old tree fern stump. Lundburg points to ferns sprouting from a fallen 'öhi'a log. It's a "nurse log," she says — a natural incubator for seeds that have dropped into it. Looking skyward, we spot an 'io, a Hawaiian hawk —the guardian of the forest — perched on a dead 'öhi'a snag, scoping out its new and developing habitat.

In 2015 Lundburg donated a perpetual conservation easement for Niupe'a to the Hawaiian Islands Land Trust, which means she and all future owners of the property give up any development rights so that it will remain conservation land. "I became a tree hugger a long time ago," she says, surveying the young grove growing in an area of native forest once deemed on the verge of being lost. "Seeing these trees now is such a validation that it was worth it," says Lundburg, who was honored as the Hämäkua Soil and Water Conservation District's 2015 Outstanding Forester of the Year.

A Family Legacy

Dianne and Francis Higgins developed an appreciation for native forest after staying at the cabins at Kalöpä State Park near their home in Pa'auilo Mauka. "Just seeing those old trees took our breath away," says Dianne. The couple moved to Hawai'i Island from O'ahu in 1992. Francis had retired from the Honolulu Fire Department in 1990, and Dianne, who had been a counselor at Leeward Community College, took a job with Kamehameha Schools. They built their solar-powered house on a secluded, seven-acre lot that was mostly pastureland.

"I wanted a place that, when we had grandchildren, they could come and it would be a home in the country, not the city," Dianne says. Over the past twenty-five years they've created lots of happy memories here: Tetherball is set up in the yard, and there's a dartboard on the länai. Out back, at the foot of their sloping yard, is their living legacy: more than one thousand native trees and shrubs across 2.6 acres that they planted with their three children and four grandchildren.

"It was a lot more work than we anticipated," says Dianne. "But once you start it, you start it. You're on a roll."

She jokes that according to her Myers-Briggs personality test, farmer-forester is among the last suitable occupations for her type. (She even wrote an article for the Farm Service Agency newsletter about their experience titled "CREP! What Was I Thinking?") "The hardest part is the removal of invasive weeds. You think you got it and it just comes back again," says Francis, recounting his ongoing battle with stubborn wainaku grass, which has roots that can grow longer than twenty feet.

As we take in the view of their young forest, Dianne lists books that inspired them and references that taught them how to become citizen foresters. She shows me a worn copy of Weeds of Hawai'i's Pastures and Natural Areas. "You can look at the pictures and look in your pasture and go, 'Does this look like that weed?'" Their self-study and persistence through rounds of trial and error have paid off, though. Their 'öhi'a trees are flourishing, growing alongside native koai'e, 'iliahi (sandalwood), köpiko and hö'awa. Francis harvests some mämaki leaves for me to take home and make medicinal tea. On their länai, two trays of 'öhi'a that Francis sprouted from seed are thriving.

"It's fulfilling to know we're doing something to help the native birds and bats and to bring back the gulch," says Dianne. "As corny as it sounds, I really do want to care for the Earth." It's a prevalent attitude, she says, among the Hämäkua community. "Even though this place is remote, in many ways it's at the forefront of restoring the environment. Community members always volunteer to help," she continues. "They care about what happens to the land."

CREP team member and statewide service forester Malia Nanbara is grateful that the program can help these passionate individuals reforest their land. Though still few in number, their enthusiasm really is contagious, she says. "They get excited, and they're really proud of what they've achieved. You can see it on their faces when they walk you over and they say, 'Remember that last time you were here and this was just a little seedling? Now look, it's taller than you!'"